Hello and welcome to Fairy Tale Friday. Are you sitting comfortably? Good. Then I’ll begin.

This is the tale I have been waiting to share. It is

one of my absolute favourite Snow White tales. It is completely bonkers, and I adore

it. It is a mix of fantasy, horror and religion.

Today’s story is by one of my favourite authors--Tanith

Lee. According to Wikipedia:

Tanith Lee was a British science fiction

and fantasy writer. She wrote more than 90 novels and 300 short stories, and

was the winner of multiple World Fantasy Society Derleth Awards, the World

Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award and the Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime

Achievement in Horror. Additionally, she wrote two episodes of the BBC science fiction

series Blake's 7. (Which the Amazing Spiderman informs me were

two of the best episodes.) She was the

first woman to win the British Fantasy Award best novel award for her book Death's

Master in 1980.

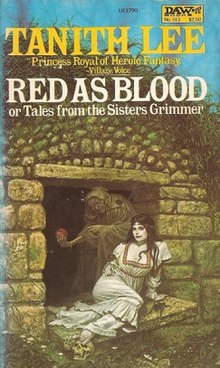

This story comes from the marvellous collection of dark

fantasy retellings of fairy tales entitled Red as Blood, or Tales from the

Sisters Grimmer. The story we are looking at today was nominated for a Nebula

Award. You may also remember me mentioning this book a few years ago when

we looked at her story Wolfland when we were exploring Little Red Riding Hood.

You can read about Wolfland {HERE}

This amazing story inverts any version I have ever

read and turns it on its head. We normally see the queen as vain and jealous

and the beautiful daughter as innocent. But not here. Here we have a concerned

stepmother who is very worried about her young stepdaughter Bianca who does not

like the day, refuses to wear a crucifix and crucially: her reflection does not

appear in the magic mirror.

Yup. You guessed it. She is a vampire. Just like her

dead mother.

Here, the good woman- a woman of faith- in an attempt

to save her stepdaughter after a wasting sickness has appeared in land (one

that has not been seen since her mother died) calls on Satan (who is the dark

side of God) to help her disguise herself and help the child. The young woman, having

had sex with the huntsman sent to kill her has now bewitched 7 black gnarled

trees as her protectors instead of dwarfs.

The old crone gives her three gifts the last one being

the scarlet fruit of Eve, the apple red as blood. Bianca chokes on it

for a very surprising reason and the Prince is not the prince you expect. It all

ends with a bit of resetting the clocks and time alteration.

This is a well told story…completely bonkers marrying the religious imagery with folklore. I really love the idea of Bianca being a vampire and would loved to have seen more of this and explored it further. Next week’s graphic novel does just this, so if you are feeling it too—stay tuned. But the religious ending as a weird sort of redemption doesn’t feel like a let down either. It makes perfect sense for the 14th century when this tale is set. I always think it will make me feel let down as I reread it, but it never does. I always feel like the ending is exactly where it should be.

Red

as Blood source

The beautiful Witch Queen flung open the

ivory case of the magic mirror. Of dark gold the mirror was, dark gold as the

hair of the Witch Queen that poured down her back. Dark gold the mirror was,

and ancient as the seven stunted black trees growing beyond the pale blue glass

of the window.

"Speculum, speculum," said the

Witch Queen to the magic mirror. "Dei gratia."

"Volente Deo. Audio."

"Mirror," said the Witch Queen.

"Whom do you see?"

"I see you, mistress," replied

the mirror. "And all in the land. But one."

"Mirror, mirror, who is it you do not

see?"

"I do not see Bianca."

The Witch Queen crossed herself. She shut

the case of the mirror and, walking slowly to the window, looked out at the old

trees through the panes of pale blue glass.

Fourteen years ago, another woman had

stood at this window, but she was not like the Witch Queen. The woman had black

hair that fell to her ankles; she had a crimson gown, the girdle worn high

beneath her breasts, for she was far gone with child. And this woman had thrust

open the glass casement on the winter garden, where the old trees crouched in

the snow. Then, taking a sharp bone needle, she had thrust it into her finger

and shaken three bright drops on the ground. "Let my daughter have,"

said the woman, "hair black as mine, black as the wood of these warped and

arcane trees. Let her have skin like mine, white as this snow. And let her have

my mouth, red as my blood." And the woman had smiled and licked at her

finger. She had a crown on her head; it shone in the dusk like a star. She

never came to the window before dusk; she did not like the day. She was the

first Queen, and she did not possess a mirror.

Seven years went by. The King married the

second Queen, as unlike the first as frankincense to myrrh.

"And this is my daughter," said

the King to his second Queen.

There stood a little girl child, nearly

seven years of age. Her black hair hung to her ankles, her skin was white as

snow. Her mouth was red as blood, and she smiled with it.

"Bianca," said the King, "you

must love your new mother."

Bianca smiled radiantly. Her teeth were

bright as sharp bone needles.

"Come," said the Witch Queen,

"come, Bianca. I will show you my magic mirror."

"Please, Mama," said Bianca

softly, "I do not like mirrors."

"She is modest," said the King.

"And delicate. She never goes out by day. The sun distresses her."

That night, the Witch Queen opened the

case of her mirror.

"Mirror, whom do you see?"

"I see you, mistress. And all in the

land. But one."

"Mirror, mirror, who is it you do not

see?"

"I do not see Bianca."

The second Queen gave Bianca a tiny

crucifix of golden filigree. Bianca would not accept it. She ran to her father

and whispered: "I am afraid. I do not like to think of Our Lord dying in

agony on His cross. She means to frighten me. Tell her to take it away."

The second Queen grew wild white roses in

her garden and invited Bianca to walk there after sundown. But Bianca shrank

away.

She whispered to her father: "The

thorns will tear me. She means me to be hurt."

When Bianca was twelve years old, the

Witch Queen said to the King, "Bianca should be confirmed so that she may

take Communion with us."

"This may not be," said the

King. "I will tell you, she has not even been christened, for the dying

word of my first wife was against it. She begged me, for her religion was

different from ours. The wishes of the dying must be respected."

"Should you not like to be blessed by

the church," said the Witch Queen to Bianca. "To kneel at the golden

rail before the marble altar. To sing to God, to taste the ritual bread and sip

the ritual wine."

"She means me to betray my true

mother," said Bianca to the King. "When will she cease tormenting

me?"

The day she was thirteen, Bianca rose from

her bed, and there was a red stain there, like a red, red flower.

"Now you are a woman," said her

nurse.

"Yes," said Bianca. And she went

to her true mother's jewel box, and out of it she took her mother's crown and

set it on her head.

When she walked under the old black trees

in the dusk, the crown shone like a star.

The wasting sickness, which had left the

land in peace for thirteen years, suddenly began again, and there was no cure.

The Witch Queen sat in a tall chair before

a window of pale green and dark white glass, and in her hands she held a Bible

bound in rosy silk.

"Majesty," said the huntsman,

bowing very low.

He was a man, forty years old, strong and

handsome, and wise in the hidden lore of the forests, the occult lore of the

earth. He would kill too, for it was his trade, without faltering. The slender

fragile deer he could kill, and the moonwinged birds, and the velvet hares with

their sad, foreknowing eyes. He pitied them, but pitying, he killed them. Pity

could not stop him. It was his trade.

"Look in the garden," said the

Witch Queen.

The hunter looked through a dark white

pane. The sun had sunk, and a maiden walked under a tree.

"The Princess Bianca," said the

huntsman.

"What else?" asked the Witch

Queen.

The huntsman crossed himself.

"By Our Lord, Madam, I will not

say."

"But you know."

"Who does not?"

"The King does not."

"Or he does."

"Are you a brave man?" asked the

Witch Queen.

"In the summer, I have hunted and

slain boar. I have slaughtered wolves in winter."

"But are you brave enough?"

"If you command it, Lady," said

the huntsman, "I will try my best."

The Witch Queen opened the Bible at a certain place, and out of it she drew a flat silver crucifix, which had been resting against the words: Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night… Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness.

The huntsman kissed the crucifix and put

it about his neck, beneath his shirt.

"Approach," said the Witch

Queen, "and I will instruct you in what to say."

Presently, the huntsman entered the garden, as the stars were burning up in the sky. He strode to where Bianca stood under a stunted dwarf tree, and he kneeled down.

"Princess," he said.

"Pardon me, but I must give you ill tidings."

"Give them then," said the girl,

toying with the long stem of a wan, night-growing flower which she had plucked.

"Your stepmother, that accursed,

jealous witch, means to have you slain. There is no help for it but you must

fly the palace this very night. If you permit, I will guide you to the forest.

There are those who will care for you until it may be safe for you to

return."

Bianca watched him, but gently,

trustingly.

"I will go with you, then," she

said.

They went by a secret way out of the

garden, through a passage under the ground, through a tangled orchard, by a

broken road between great overgrown hedges.

Night was a pulse of deep, flickering blue when they came to the forest. The branches of the forest overlapped and intertwined like leading in a window, and the sky gleamed dimly through like panes of blue-coloured glass.

"I am weary," sighed Bianca.

"May I rest a moment?"

"By all means," said the

huntsman. "In the clearing there, foxes come to play by night. Look in

that direction, and you will see them."

"How clever you are," said

Bianca. "And how handsome."

She sat on the turf, and gazed at the

clearing.

The huntsman drew his knife silently and

concealed it in the folds of his cloak. He stopped above the maiden.

"What are you whispering?"

demanded the huntsman, laying his hand on her wood-black hair.

"Only a rhyme my mother taught

me."

The huntsman seized her by the hair and

swung her about so her white throat was before him, stretched ready for the

knife. But he did not strike, for there in his hand he held the dark golden

locks of the Witch Queen, and her face laughed up at him and she flung her arms

about him, laughing.

"Good man, sweet man, it was only a

test of you. Am I not a witch? And do you not love me?"

The huntsman trembled, for he did love

her, and she was pressed so close her heart seemed to beat within his own body.

"Put away the knife. Throw away the

silly crucifix. We have no need of these things. The King is not one half the

man you are."

And the huntsman obeyed her, throwing the

knife and the crucifix far off among the roots of the trees. He gripped her to

him, and she buried her face in his neck, and the pain of her kiss was the last

thing he felt in this world.

The sky was black now. The forest was

blacker. No foxes played in the clearing. The moon rose and made white lace

through the boughs, and through the backs of the huntsman's empty eyes. Bianca

wiped her mouth on a dead flower.

"Seven asleep, seven awake,"

said Bianca. "Wood to wood. Blood to blood. Thee to me."

There came a sound like seven huge rendings, distant by the length of several trees, a broken road, an orchard, an underground passage. Then a sound like seven huge single footfalls. Nearer. And nearer.

Hop, hop, hop, hop. Hop, hop, hop.

In the orchard, seven black shudderings.

On the broken road, between the high

hedges, seven black creepings.

Brush crackled, branches snapped.

Through the forest, into the clearing, pushed seven warped, misshapen, hunched-over, stunted things. Woody-black mossy fur, woody-black bald masks. Eyes like glittering cracks, mouths like moist caverns. Lichen beards. Fingers of twiggy gristle. Grinning. Kneeling. Faces pressed to the earth.

"Welcome," said Bianca.

The Witch Queen stood before a window of

glass like diluted wine. She looked at the magic mirror.

"Mirror. Whom do you see?"

"I see you, mistress. I see a man in

the forest. He went hunting, but not for deer. His eyes are open, but he is

dead. I see all in the land. But one."

The Witch Queen pressed her palms to her

ears.

Outside the window the garden lay, empty

of its seven black and stunted dwarf trees.

"Bianca," said the Queen.

The windows had been draped and gave no

light. The light spilled from a shallow vessel, light in a sheaf, like the

pastel wheat. It glowed upon four swords that pointed east and west, that

pointed north and south.

Four winds had burst through the chamber,

and three arch-winds. Cool fires had risen, and parched oceans, and the

gray-silver powders of Time.

The hands of the Witch Queen floated like

folded leaves on the air, and through dry lips the Witch Queen chanted.

"Pater omnipotens, mittere digneris

sanctum Angelum tuum de Infernis."

The light faded, and grew brighter.

There, between the hilts of the four

swords, stood the Angel Lucefiel, somberly gilded, his face in shadow, his

golden wings spread and blazing at his back.

"Since you have called me, I know

your desire. It is a comfortless wish. You ask for pain."

"You speak of pain, Lord Lucefiel,

who suffer the most merciless pain of all. Worse than the nails in the feet and

wrists. Worse than the thorns and the bitter cup and the blade in the side. To

be called upon for evil's sake, which I do not, comprehending your true nature,

son of God, brother of The Son."

"You recognize me, then. I will grant

what you ask."

And Lucefiel (by some named Satan, Rex

Mundi, but nevertheless the left hand, the sinister hand of God's design)

wrenched lightning from the ether and cast it at the Witch Queen.

It caught her in the breast. She fell.

The sheaf of light towered and lit the

golden eyes of the Angel, which were terrible, yet luminous with compassion, as

the swords shattered and he vanished.

The Witch Queen pulled herself from the

floor of the chamber, no longer beautiful, a withered, slobbering hag.

Into the core of the forest, even at noon,

the sun never shone. Flowers propagated in the grass, but they were colourless.

Above, the black-green roof hung down nets of thick, green twilight through

which albino butterflies and moths feverishly drizzled. The trunks of the trees

were smooth as the stalks of underwater weeds. Bats flew in the daytime, and

birds who believed themselves to be bats.

There was a sepulchre, dripped with moss.

The bones had been rolled out, had rolled around the feet of seven twisted

dwarf trees.

They looked like trees. Sometimes they

moved. Sometimes something like an eye glittered, or a tooth, in the wet

shadows.

In the shade of the sepulchre door sat

Bianca, combing her hair.

A lurch of motion disturbed the thick

twilight.

The seven trees turned their heads.

A hag emerged from the forest. She was

crook-backed and her head was poked forward, predatory, withered, and almost hairless,

like a vulture's.

"Here we are at last," grated

the hag, in a vulture's voice.

She came closer, and cranked herself down

on her knees, and bowed her face into the turf and the colourless flowers.

Bianca sat and gazed at her. The hag

lifted herself. Her teeth were yellow palings.

"I bring you the homage of witches,

and three gifts," said the hag.

"Why should you do that?"

"Such a quick child, and only

fourteen years. Why? Because we fear you. I bring you gifts to curry favour."

Bianca laughed. "Show me."

The hag made a pass in the green air. She

held a silken cord worked curiously with plaited human hair.

"Here is a girdle which will protect

you from the devices of priests, from crucifix and chalice and the accursed

holy water. In it are knotted the tresses of a virgin, and of a woman no better

than she should be, and of a woman dead. And here—" a second pass and a

comb was in her hand, lacquered blue over green—"a comb from the deep sea,

a mermaid's trinket, to charm and subdue. Part your locks with this, and the

scent of ocean will fill men's nostrils and the rhythm of the tides their ears,

the tides that bind men like chains. Last," added the hag, "that old

symbol of wickedness, the scarlet fruit of Eve, the apple red as blood. Bite,

and the understanding of sin, which the serpent boasted of, will be made known

to you." And the hag made her last pass in the air and extended the apple,

with the girdle and the comb, toward Bianca.

Bianca glanced at the seven stunted trees.

"I like her gifts, but I do not quite

trust her."

The bald masks peered from their shaggy

beardings. Eyelets glinted. Twiggy claws clacked.

"All the same," said Bianca.

"I will let her tie the girdle on me, and comb my hair herself."

The hag obeyed, simpering. Like a toad she

waddled to Bianca. She tied on the girdle. She parted the ebony hair. Sparks

sizzled, white from the girdle, peacock's eye from the comb.

"And now, hag, take a little bite of

the apple."

"It will be my pride," said the

hag, "to tell my sisters I shared this fruit with you." And the hag

bit into the apple, and mumbled the bite noisily, and swallowed, smacking her

lips.

Then Bianca took the apple and bit into

it.

Bianca screamed—and choked.

She jumped to her feet. Her hair whirled about her like a storm cloud. Her face turned blue, then slate, then white again. She lay on the pallid flowers, neither stirring nor breathing.

The seven dwarf trees rattled their limbs

and their bear-shaggy heads, to no avail. Without Bianca's art they could not

hop. They strained their claws and ripped at the hag's sparse hair and her

mantle. She fled between them. She fled into the sunlit acres of the forest,

along the broken road, through the orchard, into a hidden passage.

The hag reentered the palace by the hidden

way, and the Queen's chamber by a hidden stair. She was bent almost double. She

held her ribs. With one skinny hand she opened the ivory case of the magic

mirror.

"Speculum, speculum. Dei gratia. Whom

do you see?"

"I see you, mistress. And all in the

land. And I see a coffin."

"Whose corpse lies in the

coffin?"

"That I cannot see. It must be

Bianca."

The hag, who had been the beautiful Witch

Queen, sank into her tall chair before the window of pale, cucumber green and

dark white glass. Her drugs and potions waited, ready to reverse the dreadful

conjuring of age the Angel Lucefiel had placed on her, but she did not touch

them yet.

The apple had contained a fragment of the

flesh of Christ, the sacred wafer, the Eucharist.

The Witch Queen drew her Bible to her and

opened it randomly.

And read, with fear, the word: Resurcat.

It appeared like glass, the coffin, milky

glass. It had formed this way. A thin white smoke had risen from the skin of

Bianca. She smoked as a fire smokes when a drop of quenching water falls on it.

The piece of Eucharist had stuck in her throat. The Eucharist, quenching water

to her fire, caused her to smoke.

Then the cold dews of night gathered, and

the colder atmospheres of midnight. The smoke of Bianca's quenching froze about

her.

Frost formed in exquisite silver

scroll-work all over the block of misty ice that contained Bianca.

Bianca's frigid heart could not warm the

ice. Nor the sunless, green twilight of the day.

You could just see her, stretched in the

coffin, through the glass. How lovely she looked, Bianca. Black as ebony, white

as snow, red as blood.

The trees hung over the coffin. Years

passed. The trees sprawled about the coffin, cradling it in their arms. Their

eyes wept fungus and green resin. Green amber drops hardened like jewels in the

coffin of glass.

"Who is that lying under the

trees?" the Prince asked, as he rode into the clearing.

He seemed to bring a golden moon with him,

shining about his golden head, on the golden armour and the cloak of white

satin blazoned with gold and blood and ink and sapphire. The white horse trod

on the colourless flowers, but the flowers sprang up again when the hoofs had

passed. A shield hung from the saddle-bow, a strange shield. From one side it

had a lion's face, but from the other, a lamb's face.

The trees groaned, and their heads split

on huge mouths.

"Is this Bianca's coffin?" asked

the Prince.

"Leave her with us," said the

seven trees. They hauled at their roots. The ground shivered. The coffin of

ice-glass gave a great jolt, and a crack bisected it. Bianca coughed.

The jolt had precipitated the piece of

Eucharist from her throat.

Into a thousand shards the coffin

shattered, and Bianca sat up. She stared at the Prince, and she smiled.

"Welcome, beloved," said Bianca.

She got to her feet, and shook out her

hair, and began to walk toward the Prince on the pale horse.

But she seemed to walk into a shadow, into

a purple room, then into a crimson room whose emanations lanced her like

knives.

Next she walked into a yellow room where

she heard the sound of crying, which tore her ears. All her body seemed

stripped away; she was a beating heart. The beats of her heart became two

wings. She flew. She was a raven, then an owl. She flew into a sparkling pane.

It scorched her white. Snow white. She was a dove.

She settled on the shoulder of the Prince

and hid her head under her wing. She had no longer anything black about her,

and nothing red.

"Begin again now, Bianca," said

the Prince. He raised her from his shoulder. On his wrist there was a mark. It

was like a star. Once a nail had been driven in there.

Bianca flew away, up through the roof of

the forest. She flew in at a delicate wine window. She was in the palace. She

was seven years old.

The Witch Queen, her new mother, hung a

filigree crucifix around her neck.

"Mirror," said the Witch Queen.

"Whom do you see?"

"I see you, mistress," replied

the mirror. "And all in the land. I see Bianca."

That’s all for this week. Stay tuned for a graphic

novel that was definitely influenced by this story.

No comments:

Post a Comment